Learning from the Disability Justice movement

Since becoming chronically ill with Long COVID and identifying as Disabled, I’ve been on multiple simultaneous journeys – one of which has been diving into concepts of Disability Justice. I’m still learning and unlearning, but in this post I share some concepts and sources of information that have furthered my understanding and liberation. Ideas which now guide how I engage with activism, dreaming of a better world, and bringing that better way to life.

I’ve included a lot of different ideas and concepts to take in and think on, here. It’s too much to make sense of in one sitting, so feel free to return to this blog if you need to. It will be here.

I encourage you to check in with yourself as you read and learn. Reflect on any resistance that arises. Be aware of tension, tough feelings, or the lack thereof. It’s important to check in with our bodies and engage in embodiment practices when we learn things that challenge the status quo and highlight our complicity – this is true especially as white people when we engage with work on anti-racism. And that is a part of Disability Justice. Without these skills of embodiment and regulation, we cannot honestly contend with hard questions and the need for accountability and change. And we cannot join in on the good being done to build a better world for all bodies.

Without further ado, here are some starting concepts to chew on and dig further into on the topic of Disability Justice.

Disability Justice is a movement borne of Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities of queer and femme Disabled people.

“A Disability Justice framework understands that:

- All bodies are unique and essential.

- All bodies have strengths and needs that must be met.

- We are powerful, not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them.

- All bodies are confined by ability, race, gender, sexuality, class, nation state, religion, and more, and we cannot separate them.”1

Sins Invalid cofounder and executive director, Patty Berne, writes:

“We cannot comprehend ableism without grasping its interrelations with heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism and capitalism. Each system benefits from extracting profits and status from the subjugated ‘other’. 500+ years of violence against black and brown communities includes 500+ years of bodies and minds deemed ‘dangerous’ by being non-normative.”2

Disability Justice differs from the Disability rights movement – a movement which has many unresolved issues, as Patty Berne explains: “Disability rights is based in a single-issue identity, focusing exclusively on disability at the expense of other intersections of race, gender, sexuality, age, immigration status, religion, etc. Its leadership has historically centered white experiences and doesn’t address the ways white disabled people can still wield privilege. It centers people with mobility impairments, marginalizing other types of disability and/or impairment.”3

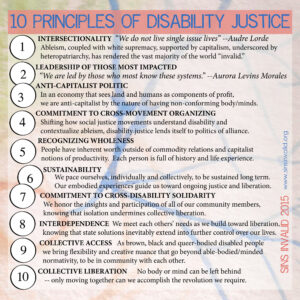

To better understand Disability Justice let’s look at the 10 Principles of Disability Justice from Sins Invalid4:

ID: Blue text heading highlighted in pink reads: 10 Principles of Disability Justice. Black text on pale yellow background reads the list of the ten principles. Full Text of image.

This 3 minute video by writer, educator, and community organizer for disability justice and transformative justice, Mia Mingus, is another source explaining facets of Disability Justice: Mia Mingus on Disability Justice

Medical Model of Disability vs Social Model of Disability

Generally speaking, we are all formed in society through the lens of the medical model of disability. This is a key point of unlearning. We need to consider the ways in which this model marginalizes, harms, and reinforces ableism in our relationships, communities, and systems – including the medical system.

Critiques of the medical model include5:

- It positions Disabled bodyminds as “wrong”, “broken”, or “abnormal”. Positioning disability as abnormal causes a lot of problems and is a foundation for ableism. The concepts of “disability” and “disease” are socially constructed and this model does not acknowledge that.

- It medicalizes the existence of Disabled people and strips them of agency.

Critiques of the social model include5:

- It doesn’t hold space for distress as a result of disability, including the existence of pain, fatigue, and other symptoms of chronic illness that are not necessarily solved by removing societal barriers.

As I understand it, the social model of disability suggests that if we address everyone’s access needs, they are no longer Disabled. However, this can be reductionist. There are aspects of illness and disability that are not eliminated by meeting my needs and changing our systems, such as the fatigue and exertion intolerances that cause me to get sicker when I over-exert. Perhaps, the social model says a more just world would include adequate supports for these distressing symptoms and adequate funding for the discovery of effective treatments and cures for chronic illnesses. But the point is, like with most things, one model does not necessarily fit all.

Other concepts to consider related to disability and the principles of Disability Justice:

Ableism

- We all have ableism within us to contend with. It is not something that happens “over there”. We have all been formed in ableism similar to how most of us have been formed in white supremacy. We experience both internalized ableism and external interpersonal, systemic, and structural ableism.

- Disabled bodyminds are a part of human diversity and are not uncommon or rare. In fact, the number of Disabled people is growing all the time in this world of pandemic and climate change.

- The opposite of disabled is enabled. A lesson from english grammar that I find drives a great point in line with the social model of disability.

- Disabled people are not a monolith. There are many different Disabled experiences. There are many different access needs. We have differing needs, opinions, experiences, skills and expertises, just like any human does.

- Not all disabilities are “visible”. There are many invisible disabilities. Invisibly Disabled people exist in your workplaces, your friendships, your families, your communities. If you think you don’t know a Disabled person, you’re wrong.

- Disabled people with invisible disability and/or illness often endure ableism by way of comments like, “But you don’t look sick/disabled/____!” or “You don’t need that wheelchair/aid/support/____.” It’s found in comments suggesting people are faking or trying to “take advantage” of support systems (this one clearly shows people’s ignorance as adequate supports for Disabled people do not exist and the ones that do are extremely gatekept and very difficult to access!)

- Disability has nothing to do with effort. In fact, everything about life and living in this abelist society requires far more effort placed directly on the ‘shoulders’ of Disabled bodyminds.

- Healthcare and medical systems are very dangerous for Disabled bodyminds. These systems, professions, and environments are steeped in ableism – both overt and covert, systemic/systematic and interpersonal, extrinsic and intrinsic.

- Non-disabled, or able-bodied, bodyminds are the gatekeepers of resources – that’s how we’ve built our society but it does not have to be this way. Non-disabled people tend to think they know best what Disabled people need. Ableism in this way is seen in lack of humility, lack of ability to admit knowledge gaps, and the de-centering of Disabled expertise. Lenses like these lead to labelling people as “malingering”, “faking”, or “psychosomatic” when an illness or set of symptoms are not understood or do not easily fit a textbook definition. Paternalization and infantilization is commonplace and baked into our systems and our society. The gatekeeping of resources is just one example.

- There are many people who have not accessed diagnosis and adequate healthcare. Multiple intersections are important to note here: medical racism and systemic barriers to healthcare, societal stigma, medical trauma, medical misogyny.

- Healthcare providers label people with diagnoses – they don’t tell people they are Disabled. Instead, “Disabled” is an identity and a community we claim membership of as we understand it for ourselves and in community with others.

Language and Euphemisms

- “Disabled” is not a bad word. There are many harmful euphemisms created by and largely used by non-disabled people that were borne out of ableism. Terms like “differently abled”, “handi-capable”, and “special needs” are dehumanizing, infantilizing, and deflect from real experiences and needs. These terms tend to center stories of “overcoming”, stories of “pity”, and the discomfort of non-disableds, instead of centering the full, complex experiences of Disabled community and our preferred terms.

- Person-first language (ie. “person with a disability”; “person with Autism”) is distinct from identity-first language (ie. “Disabled person”; “Autistic person”). Person-first language is kind of related to the harmful euphemisms limited above, but I consider it a far lesser evil. Regardless, I find it still centers non-disabled discomfort and pushes a narrative that disability is an abnormality we should be ashamed of and should be trying to “overcome”. Some Disabled people are okay with and even prefer to use person-first language, though. Ultimately, what is most important is to confirm how someone identifies and to take their lead, while also remembering not every Disabled person identifies in the same way. I prefer identity-first language (ie. Disabled person) rather than person-first language because being Disabled is a central part of my identity and it is nothing to be ashamed of. It does not take away from my personhood. It is a central part of my personhood.

Meeting Access Needs

- Competing access needs exist. I think of examples like heat intolerance making an air-conditioned indoor setting more accessible in the summer, versus the immunocompromised reality of many of us in a pandemic situation where no one is wearing masks and there are no air filtration systems implemented means an outdoor setting is an access need. These competing needs can exist within us (ie. having to choose which of the above two needs to prioritize), as well as exist between people with different access needs. To make spaces safe and accessible requires ongoing conversation and collaboration. Also, environments do not become accessible with the addition of a ramp!

In the fall of 2022, I spoke to our faith community about the above concepts and more. (Cypher Church and A Beautiful Table gather online twice monthly). If you have experience in faith communities or religion, but even if you don’t (because these ideas also pervade our larger Western culture), here are some more ideas to consider around the concepts of healing and prayer (please consider this a content warning!):

Resurrected bodies and “no more suffering”

- If Disabled bodies are created beautiful and in God’s image; if Disabled bodies are a part of human diversity; if disability is largely created and caused by an unjust society (see the social model of disability) – then perhaps the healing that occurs is a healing of systems and structures that cause barriers to full belonging. The idea that a thin, young, white, non-disabled bodymind is the ideal is socially constructed. We made that. We can unmake it, too. A related idea: if we get to live to an old age, does our “healed”, resurrected body become the “perfect” young (ie. 25 year old) version society says we should be? The things that we have socially constructed as “wrong” (ie. age, body shape and size, ability, etc.) cannot be mistakes that require “correction” by a God who created us in their image. Does not compute.

- I will say, though, I’d like my body to recover and be “healed” because the symptoms of this chronic illness are suffering in and of themselves. Some of my suffering would be alleviated if capitalism, heteropatriarchy & misogyny, ableism ceased to exist – but I’d still have signifiant fatigue, post exertional malaise, etc.

Prayer

- It is too often used as a placeholder for actively meeting needs. We too often try to “pray away” things like disability, access needs, and more, rather than simply asking people what they need and actually addressing it along with them.

- It’s also weaponized very often – even when unintentional. Maybe especially when unintentional. People use prayer to “encourage” someone, or pray for someone without their consent. People pray for things that someone has not asked them to pray for. People suggest that someone’s “sin” or lack of faith is in the way of their healing. People perform “prayer sermons”6 upon others. Prayer for healing is often tied up with racism, as well. These are all examples of weaponizing prayer. They amount to spiritual abuse and religious trauma, as well as ableism, racism, misogyny, etc.

Healing

- We don’t have answers for why some people recover or are healed and some are not – both currently and historically. When I think of bible stories – and if I were to take them literally – I wonder whether stories of Jesus healing blindness wasn’t because existing as a b/Blind person is “wrong” or “broken”, but because Jesus knew they existed in a world that marginalized them. Was he choosing to ease their existence by way of providing sight in such a disabling world? That seems very medical model to me! If not downright ableist. So then, why wouldn’t Jesus heal the ableist world and systems, instead? We need those things healed far more. Is the social model of disability too big even for God? Or was Jesus also a product of a time and place when disability and illness were othered… I have some big questions around the ideas of these bible stories. [This question is answered really nicely in the first chapter of Amy Kenny’s book My Body Is Not A Prayer Request! I recommend reading it.]

Phew – that was a lot of info! These aren’t things you can unlearn/learn over night. People write full books and guides on these topics. I’ll leave you with a few of titles from which some of this blog and my own learning are derived:

Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Skin, Tooth, and Bone – The Basis of Our Movement is People: A Disability Justice Primer by Sins Invalid

My Body is Not A Prayer Request: Disability Justice in the Church by Amy Kenny

Happy learning!

References:

1Patty Berne, “Skin, Tooth, and Bone – The Basis of Our Movement is People: A Disability Justice Primer,” c. 2019 by Sins Invalid, Second Edition, p. 19.

2https://www.sinsinvalid.org/news-1/2020/6/16/what-is-disability-justice

3Patty Berne, “Skin, Tooth, and Bone – The Basis of Our Movement is People: A Disability Justice Primer,” c. 2019 by Sins Invalid, Second Edition, p. 13.

4 https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice

5 hat tip to Kaia Arrow for teaching me these critiques and providing some of the language used, here. Find Kaia on social media @TheWillowsWork or her website.

6 hat tip to Robert J Monson for the term “prayer sermons”. Find him on Twitter @RobertJMonson, via his substack, or via his podcast Three Black Men: Theology, Culture, and the World Around Us. He is also co-director of enfleshed.